“Esse est percipi (aut percipere).”

To be is to be perceived (or to perceive).

~ Bishop Berkeley (*1685; †1753)

“No phenomenon is a real phenomenon until it is an observed phenomenon.”

~ John Archibald Wheeler (*1911; †2008), Cf. “It from bit”

“Esse est percipi (aut percipere).”

To be is to be perceived (or to perceive).

~ Bishop Berkeley (*1685; †1753)

“No phenomenon is a real phenomenon until it is an observed phenomenon.”

~ John Archibald Wheeler (*1911; †2008), Cf. “It from bit”

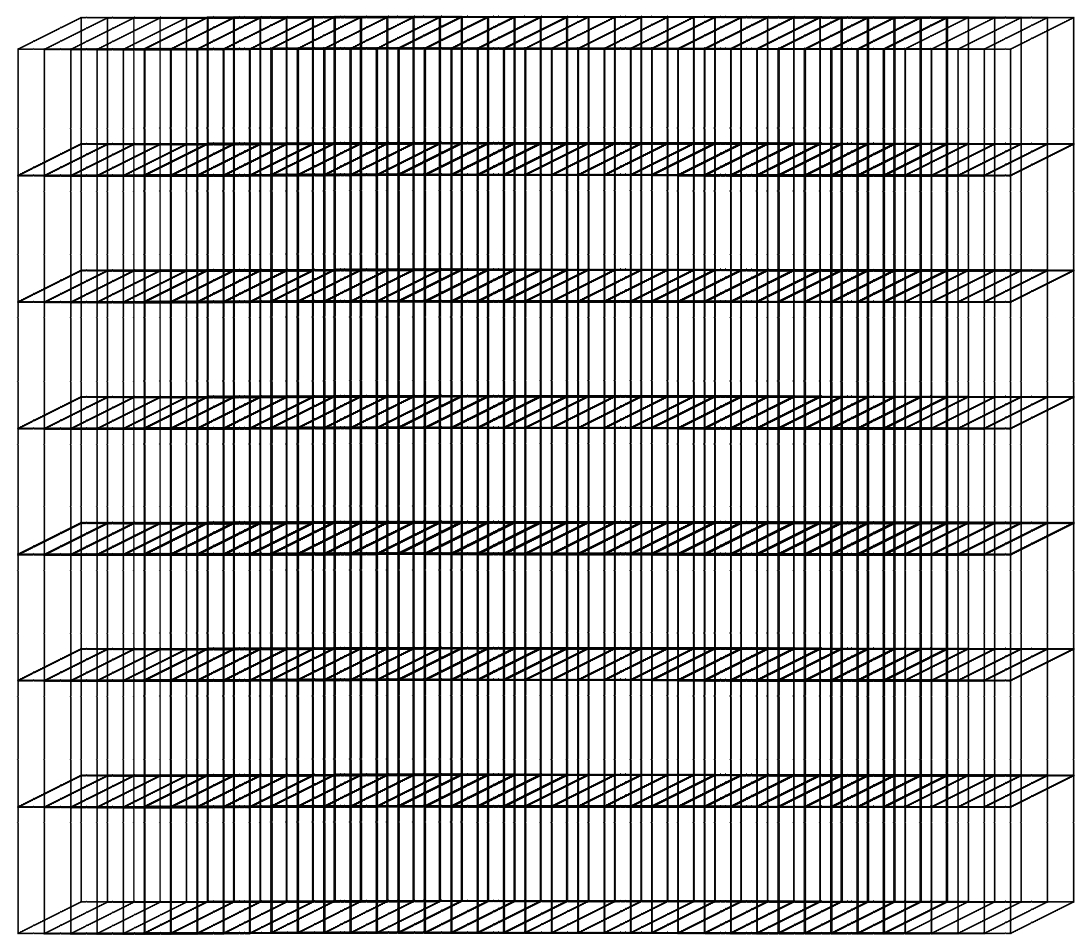

A quantum cognition perspective on the Necker cube

(lecture by Dr. Christopher Germann @ CogNovo – University of Plymouth, 2016)

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

_|_| _| _| _| _| _|_|_| _|_|_| _|_|_| _|_| _| _|_| _| _| _| _|_| _| _| _| _| _| _| _| _| _|_| _| _| _| _|_| _| _|_|_| _| _|_|_| _| _| _| |

About this website

www.Qbism.art is an interdisciplinary web-project that synthesises a plurality of perspectives from cognitive psychology, neuroscience, quantum physics, philosophy, computer science, and digital art into a holistic transdisciplinary Gestalt. You can view a series of animated digital Qbism artworks below (the neologism ‘Qbism’ is a composite lexeme composed of ‘Quantum & Cubism’).

The German “Naturphilosoph” Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling (1775—1854) stated that art is “the eternal organ and document of philosophy” which arises from an “unconscious infinity” – a synthesis between nature and freedom. His “aesthetic idealism” (System of Transcendental Idealism; 1800) was highly influential for German idealism (see: https://cognovo.net/cms/cognovo-art).

The philosopher and art historian Marshall McLuhan interpreted Cubism in the context of his conclusion that “the medium is the message“. For McLuhan, the perception of Cubist art required an “instant sensory awareness of the whole” (as opposed to perspective alone). That is, the necessary holistic interpretation of Cubist art does not allow for the question “what is the artwork about” (i.e., semantic content). Cubist art has to be perceived in its entirety (i.e., holistically).

McLuhan, M. (1946). Understanding Media: The extension Man. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1016/j.concog.2016.11.011

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Quantum physics is characterized by its paradoxical logic. Two crucial concepts in quantum logic are the interrelated concepts of complementary and superposition. These peculiar properties can can be visually illustrated by the Necker cube because two incompatible visual interpretations are in a superpositional state and they exhibit the property of complementarity. Observation plays a crucial rôle in this context as the ambiguous superpostional state collapses into an “eigenstate” (a fixed state) when it is observed. In this context Einstein famously asked the question if the moon exists when nobody looks at it – a profound question which highlights the importance of perception, observation, and measurement in physics:

We often discussed his notions on objective reality. I recall that during one walk Einstein suddenly stopped, turned to me and asked whether I really believed that the moon exists only when I look at it. The rest of this walk was devoted to a discussion of what a physicist should mean by the term “to exist”.

Einstein made a similar statement about the nature of perception and the relation between subject and object (i.e., mind & matter; knower & know; seer & seen; psyche & physis) in a discussion with the Indian polymath Ravīndranātha Ṭhākura (Tagore) which took place in his house near Berlin in 1930:

“If nobody were in the house the table would exist all the same, but this is already illegitimate from your point of view, because we cannot explain what it means, that the table is there, independently of us.”

Interestingly, the same fundamental question concerning the nature of “external reality” can be asked with respect to the perception of the Necker cube: What is the position of the Necker cube when it is not observed?

That is, what is its configuration in an unobserved state?

The nature of the seer and the seen (Sanskrit: Dṛg-Dṛśya) has been discussed since ancient times in Indian philosophy, for instance in the highly psychological text Dṛg-Dṛśya-Viveka attributed to Bâratī Tīrtha (ca. 1350 ce). Numerous famous quantum physicist (e.g., Schrödinger, Bohr, Oppenheimer, etc.) were deeply impressed by the logic of ancient Indian scholars.

Quantum physics thus revives timeless questions concerning the nature of perception and observation and it provides impetus for important questions which are relevant far beyond the domain of subatomic phenomena. It forces us to consider epistemological/ontological questions whose answers are usually uncritically taken for granted. Quantum physics shows that we are not merely passive observers of an a priori existing reality. The exact nature of this relation is a matter of an ongoing scientific debate and it is a question of great pertinence for psychology, specifically for the domain of psychophysics which focuses on sensation and perception.

“In atomic science, so removed from ordinary experience, we have received a lesson which points far beyond the domain of physics.”

In conclusion: The nature of reality is still a mystery to science, despite the significant progress which has been made in many disciplines. Intellectual humility is thus a real scientific virtue (as has already been pointed out by the ancient Greek philosophers). The fundamental questions concerning the relationship between mind and matter (i.e., psyche & physis) are not “only” of philosophical importance but they provide important impetus for the development of novel testable hypotheses and theories. The history of science has taught us an important lesson: Great discoveries are often made without the intention to develop new technologies or products. Innovative inventions are oftentimes the unpredictable byproduct of scientific inquiry into novel areas of exploration. Intrinsic curiosity is thus crucial for cognitive innovation and scientific discoveries.

According to Dirac:

“The superposition that occurs in quantum mechanics is of an essentially different nature from any occurring in the classical theory.”

Dirac, P.A.M. (1958). The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, 4th edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford UK, p. 14.

The quantum state of a given physical system is described by a wave function (an element of a projective Hilbert space).

This can be symbolically expressed in Dirac or bra–ket notation as a vector:

\({\displaystyle |\psi \rangle =\sum _{i}c_{i}|\phi _{i}\rangle .}\)The mathematical concept of a Hilbert space (eponymously named after David Hilbert) formalizes he notion of multidimensional space, i.e., space with an infinite number of dimensions. Particularly interesting from psychological/epistemological point of view because human beings experience their cognitive limitations when they try to visualize multidimensional space (that is, beyond 3-dimenisonal Euclidean space). The concept of Hilbert space thus requires us to literally think outside the 3-dimensional box — beyond the ordinary limitation of experiential space-time geometry.

Physics is to be regarded not so much as the study of something a priori given, but rather as the development of methods of ordering and surveying human experience. In this respect our task must be to account for such experience in a manner independent of individual subjective judgement and therefore objective in the sense that it can be unambiguously communicated in ordinary human language.

Nils Bohr (1960) “The Unity of Human Knowledge”

The Future of an Illusion”

Tags: Algorithmic Digital Art, Bistable perception, Cognitive Neuroscience, Cognitive psychology, Computational Physics, Computer Science, Epistemology, Neuroscience, Ontology, Philosophy of mind, Psychophysics, Quantum Bayesianism, quantum cognition, Quantum physics, Visual constructivism, Visual perception